Indigenous Writing Shortlist

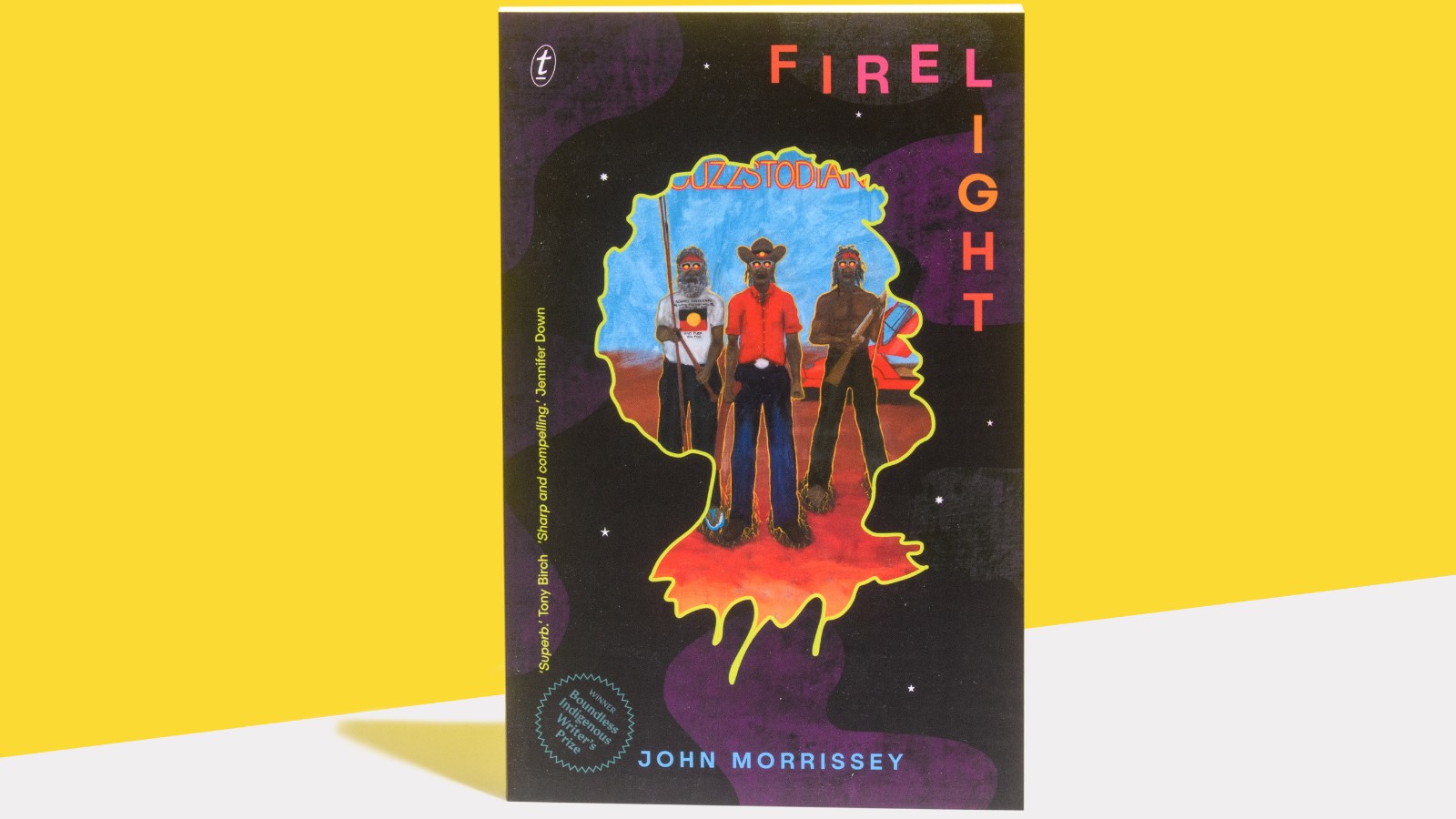

Title: Firelight

Author: John Morrissey

Publisher: Text Publishing

An imprisoned man with strange visions writes letters to his sister.

A controversial business tycoon leaves his daughter a mysterious inheritance.

A child is haunted by a green man with a message about the origins of their planet.

In this striking collection of stories, the award-winning John Morrissey investigates colonialism and identity without ever losing sight of his characters’ humanity. Brilliantly imagined and masterfully observed, Firelight marks the debut of a writer we will be reading for decades to come.

Photography by Sarah Walker

Judges’ report

Firelight weaves together wondrous reimagined worlds and real-time experiences of First Peoples in this remarkable debut collection of short stories. Kalkadoon writer John Morrissey artfully challenges structures of colonisation and centres the power of storytelling and imagination in this thrilling speculative fiction odyssey through space, time, culture and the fantastically absurd.

Extract

Tommy Norli was born on Murchison Station to a black mother and a white father. His father waited until two days after the birth to come and visit mother and child. By way of making up for his delay—or maybe for the pregnancy itself—he brought Tommy a rattle he had made from a dry gourd and a lamb’s knuckle.

Tommy liked the rattle, and carried it around with him for a long time, until one day he lost it playing in the river. Every few months or so after that, he’d jump in the water and feel around in the soft mud, trying to find it again. This was more effort than he made to find his father, who had vanished just as completely only a few weeks after Tommy entered the world.

Tommy grew up on the station, working as soon as he was old enough, doing any job he could for a little sum in addition to his two meals a day. He realised early on that he wasn’t being paid what he deserved. He often lay awake at night looking at the stars, turning this knowledge over and over in his mind with a cold satisfaction, wondering what he would do about it.

He mostly kept away from booze and didn’t bother women. Some of the white men thought he was wise in his silence. He didn’t encourage the notion, but he didn’t repudiate it either. All the while, he kept an inner tally of what he was owed and what he had been given.

One afternoon, a salesman named Jack came to the station, a white man selling flimsy tools and cheap jewellery. He told them he had been travelling for a long time. Sun and sweat had faded his shirt to colourlessness. Nobody showed much interest in what he had to sell. But night was falling, and the grazier’s house was still hours away, so the stockmen invited him to camp and have a drink with them.

That night, a hot wind coursed over the plains. Tommy sat a little distance from the fire, watching the stockmen laugh and drink, while the pale smoke climbed and dispersed into the sky. Tommy imagined warbands assembling in the darkness, beyond the ring of flushed white faces.

Jack was a quiet drinker, which led Tommy to feel a slight kinship with him. One by one, the other men staggered off to their beds; finally it was just Tommy, still sober, and Jack, surrounded by empty bottles but not even swaying where he sat.

For several minutes they were silent. The fire had dwindled to glowing coals.

Jack spoke first. ‘How long you been working out here?’

‘All my life,’ replied Tommy.

‘I need some help getting around out this way. Pay you well.’

‘How long?’

‘Long as you like.’

The idea appealed to Tommy. If Jack ever tried to short him on his wages, Tommy could just walk away, leave him out there in the bush.

That night, Tommy rolled up all his money in a piece of kangaroo hide and buried it beneath a post on the road leading to the station. He scratched an X into the post with his knife and memorised the rocks and trees around it. He had saved his wages carefully, and even with the bosses’ constant pilfering it was a substantial sum for a black to call his own.

They set off together at dawn the next day. Jack was in a good mood, and told Tommy about a pair of white men who had died following the same track nearly forty years earlier. They had come from down south, looking for the sea; but as Jack told it, they ran out of flour and sugar, and the blacks hounded them the whole way, with spears and shouts and nocturnal curses.

And Jack told him how friends of the white men had buried food for them, marking the spot with a carving on a tree, but it hadn’t been enough, they starved to death all the same. Tommy thought of his own mark, scratched on the fencepost, and swore to himself with all his strength that he would return to it.

He and Jack travelled together for six months. They rarely spoke, sometimes passing whole days in silence, Jack trudging ahead of him on the path, panting a little but driven forward by an overpowering need to sell a few trinkets at the next station. Tommy’s wages were no more than he’d got back at Murchison, but the work suited him better, as did the company. During the long silences he could sometimes convince himself that he was totally alone.

In the heart of summer they entered the mangrove swamps. Tommy was stunned by the smell of death rising from the mud, and by the abundance of life which accompanied it. It seemed he could not move a limb without disturbing some living thing. The air teemed with insects, the water with tiny fish. Birds perched on the riverbank, sunning the muck on their wings, watching the men indifferently as they passed. The swamps unnerved Tommy, and he longed to return to the calm, dry land he knew best, with its slow and measured rhythms.

At sunset one day they made their camp in a clearing by the river. Tommy built a fire as the shadows of the mangroves grew long and the moon rose in the clouds. He listened to the swallowing sounds the water made on the muddy bank, and he thought of his childhood rattle, the only token his father had left him, lost to the clammy grip of the riverbed.

They ate their dinner quickly and climbed into their swags. Tommy was comforted by the warmth of the fire on his cheek. In his head he began the Lord’s Prayer as his mother had taught it to him, but was asleep before Thy Kingdom come.

He was woken by the high, clear sound of a woman singing. Paralysed in his swag, he strained to listen. Soon the voice was joined by another, and then by another, until a chorus rose out of the dark mangroves, singing wordlessly of a misery so great that it seemed to Tommy it could only belong to the dead.

Jack stirred, and muttered, ‘What the hell is that?’

About the author

John Morrissey is a Melbourne writer of Kalkadoon descent. His work has been published in Overland, Voiceworks, Meanjin and the anthology This All Come Back Now. He was the winner of the 2020 Boundless Mentorship and the runner-up for the 2018 Nakata Brophy Prize.

Related Posts

Read

Anne-Marie Te Whiu Receives The Next Chapter Alumni Poetry Fellowship

2 Apr 2024

Read

What's on in April: Resident Organisation Round Up

28 Mar 2024

Read

Blak & Bright First Nations Literary Festival returns in 2024

7 Mar 2024

Read

What's on in March: Resident Organisation Round Up

29 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: International

23 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: The Rooms

23 Feb 2024

Share this content