Remembering Steven: A Yarra River Walk

Tony Birch walks along the Yarra River, from Kew, after stopping in at Kew Cemetry, where his childhood friend Steven – who will be his companion on the walk – is buried. He reflects on the river’s importance to the Wurundjeri people, and to him personally, as he goes.

I set out with the intention to begin my walk at the Kew Billabong (more on that later). I studied the transport maps and worked out I needed to catch the number 48 tram to Balwyn and get off at stop number 33. I’ve been feeling lightheaded and pleasantly spacey. (I have felt the world too big of late, and kept myself small.) I caught the 109 tram by mistake. I didn’t realise my error until the tram was about to verge to the right instead of ploughing straight on. I jumped off the tram and decided to walk the remaining journey. Within a few minutes, I was standing at the gates of Kew Cemetery. Not my intended destination, but the place where one of my closest teenage friends, Steven Ward, has been buried for 35 years. I loved Steven. We lived on the same public housing estate and went everywhere together; most particularly to the Yarra River, the backyard of our childhood.

Deciding I couldn’t walk by the cemetery without visiting Steven’s grave, I went inside. I had visited him many times before, and was surprised that I couldn’t locate the grave. It angered me. I felt negligent. And guilty. It was as if I had forgotten him.

Determined not to give up, I walked the lanes in the section of the cemetery where I knew Steven was resting. I passed the graves of the old and young, married couples and entire families. Just when I was about to quit the search, I found myself standing in front of Steven’s tombstone. It was a bittersweet discovery, like frantically searching for the face of a loved one in a crowd, finding that face and experiencing its disappearance at the same time. I sat down and cried, not surprisingly, and unashamedly. Was it a fortuitous detour? I guess so. After all, I had been heading to our place. There was no question that Steven would come walking with me.

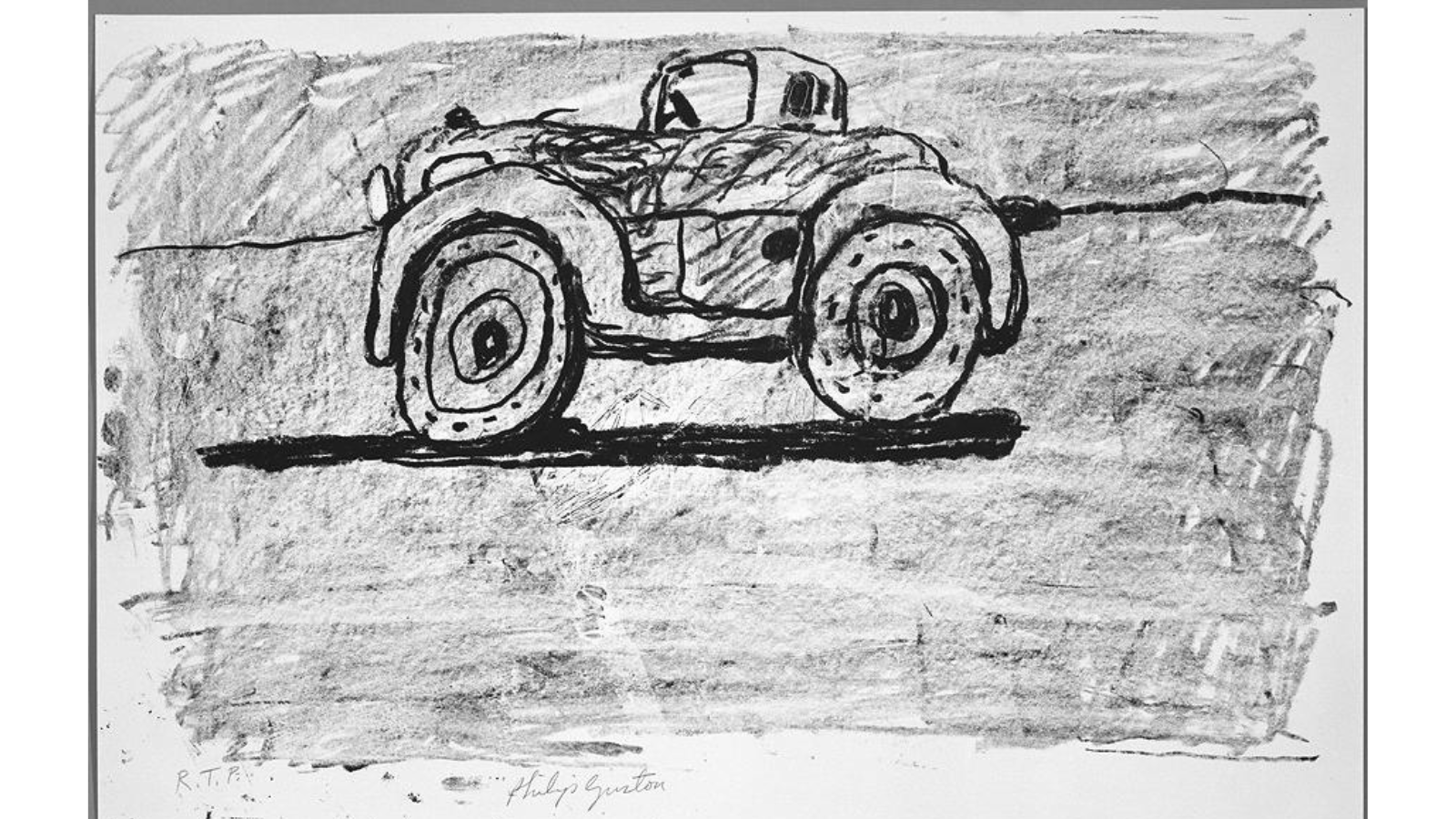

I stopped on a bridge above the Eastern Freeway – a river for cars. Victoria has a freeway fetish, matched only by our fetish for cars. I can spit further than the distance some people drive to work of a morning. A freeway flows reasonably around lunchtime when it’s quiet. During peak times, Melbourne’s freeways block up like an old sewer, and the state is forever on the lookout for solutions – of a limited kind. While Melbourne’s public transport system struggles with ageing infrastructure, each time a major road artery clogs beyond repair, we choose a bypass; a new artery with a limited lifespan before it too requires major surgery. Our latest transport solution is the proposed East-West Link, a tunnel that will burrow deep beneath the ground, welding two freeway systems together. Most cars travelling through the link on workdays will carry solitary drivers. I expect that eventually they will spend a lot of time in the tunnel talking to themselves.

It took me no time to leave the traffic behind and find myself at the Kew Billabong. The billabong is the remnant of a vast wetland that once dominated the landscape. It was home to a vast array of birds and animal species, few of which remain. (Although programs to provide a suitable habitat for birds is ongoing). The billabong is an important cultural and spiritual place for the Wurundjeri people, the Aboriginal nation of greater Melbourne. They are a remarkable community. Faced with the onslaught of the British occupation of their land from 1835, the Wurundjeri’s courage, intellect and ingenuity has ensured that their knowledge of, and claim on land remains vital to sites such as this.

When we were kids, we would ride out to the billabong on summer afternoons. The bikes we rode were put together affairs, assembled from bits and pieces we scrounged from around the streets. There were no bike paths in those days, very few people out walking their dogs, no freeways bulldozing our wayward days, and no signs welcoming visitors to Aboriginal country. But still we played the game of Aborigines every chance we got. Our blood was strong, but our skin, burnt brick-red by the sun, would never do. We would begin the game by jumping naked into the billabong, scooping up handfuls of mud at the water’s edge and smearing it across our bodies. We went black face, I guess. But all for a good cause. We were wild and did not want to be civilised or assimilated. We hid our faces from progress. In the billabong, we were safe. While we imagined spearing anyone who dare invade our country, we were sure we would never grow and never die. As long as we stayed in that water.

The billabong could not hold us, and we did grow. We roamed the river for miles and claimed all of it as our own, with little competition, as the river was unloved and neglected by others. We would sit on along her muddy bank, smoking cigarettes and singing to her. The river wanted to know that we loved her, and tested us at every opportunity. One summer we pledged to jump from each and every bridge from the city centre to the Pipe Bridge, the last bridge along the river before the billabong. Jumping into the water from 60 feet above its surface should have created fear. It never did. Even deep in the blackness and pockets of chill, I was sure the river would hold us true. If you have never jumped, let me share a secret with you. In the space between your feet leaving the safety of the railing and hitting the water, there is a moment of genuine flight – everything stops, except your imagination.

And then the saddest day arrives. Some of your river has been taken from you, and destroyed by those fools in suits who love freeways. And those other fools who would rather sit, stuck, immobilised, in capsules spewing shit into the air. Other parts of your river have been opened up with pathways, bikeways and walkways.

You have a choice. You can share the river with others, and their dogs, and their frisbees, and kites, and expensive baby strollers. Or you can leave and carry the river and the soul of your teenage friend with you. All you can do is leave behind an epitaph for those who will never know the river as you do. Maybe you don’t want to admit it. Maybe you can’t face up to a truth; these new people who come to your river may just love it too. Yes, that’s the hardest truth of all. You do not own this place. And you cannot – if what is left of the river is to be cared for and saved.

You return home, to the falls. The river you love – this is her heartbeat. As the water rushes over the falls, the vibration shakes the ground. It is good to know that she is alive. Just when you are feeling as selfish as a stupid man can be, thinking, ‘why don’t these people just fuck off and give my river back to me,’ a serendipitous sound shifts against the sandstone steps on the far bank. You think it is a trick. A deception tugging at your deep sense of loss – for your people, for your loved boyhood friend who shared the water with you with his gleaming skin and velvet hair.

But it is not a trick. It is an offering from another visitor, standing by the water offering a song. For the river. And for me. I wave across the water to him and say ‘thank you.’ I leave knowing that I am the only fool today. I am the one who needs to know. I need to know that the places we love are not ours to covet. They are not ours at all. We belong to them.

Related Posts

Read

Anne-Marie Te Whiu Receives The Next Chapter Alumni Poetry Fellowship

2 Apr 2024

Read

What's on in April: Resident Organisation Round Up

28 Mar 2024

Read

Blak & Bright First Nations Literary Festival returns in 2024

7 Mar 2024

Read

What's on in March: Resident Organisation Round Up

29 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: International

23 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: The Rooms

23 Feb 2024

Share this content