2024 Hot Desk Extract

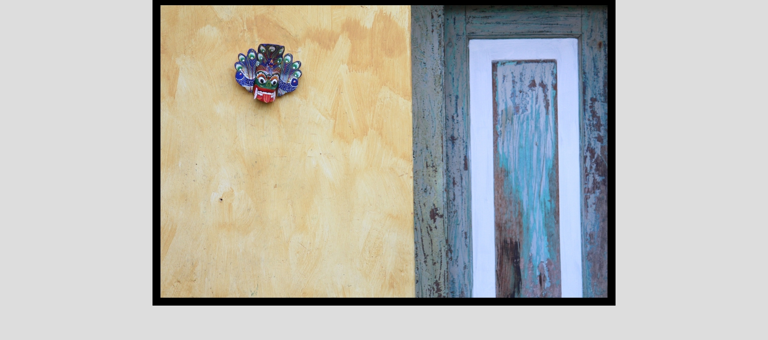

Shashini Gamage - The Fright of Real Feathers

Image Credit: Shashini Gamage

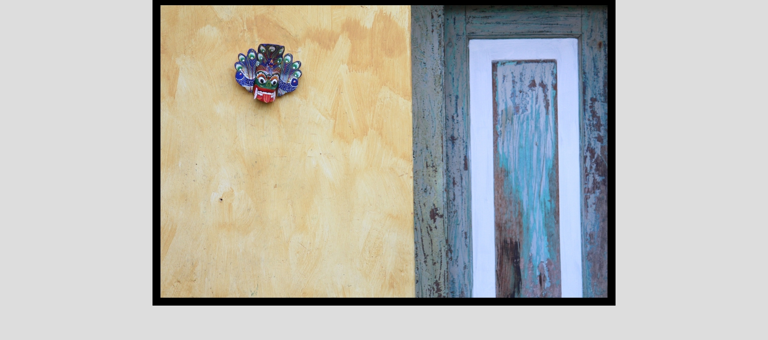

Shashini Gamage - The Fright of Real Feathers

Image Credit: Shashini Gamage

As part of The Wheeler Centre’s Hot Desk Fellowship program, Shashini Gamage worked on her debut autofiction novel The Fright of Real Feathers.

The narrative reflects on a 40-year-old Sri Lankan-Australian migrant woman returning to Sri Lanka to care for her ageing mother and discovering the truths of life, based on Shashini’s memories of growing up during the civil war in the island.

The book flows along three journeys that the narrator takes back to Sri Lanka to care for her mother. The book explores ageing parental love, how care becomes fraught with responsibilities, the influences of Buddhism on nurturing, the impact of migration on place, and how relationships grow with the life-course. More than anything, this book is about mothers and daughters.

![]()

The scar that I gave my mother from being born lives on her. I can see that scar, an eternal reminder of that fateful day, etched on her yellow skin where the buttons of her housecoat have come off as she lies on the hospital bed. She used to describe it, what she felt after waking up from the caesarean. Someone cut my belly open with a fish-machete, Ayyo, yes, a big blunt fish-machete, she said about it. My mother said that my aunt ran along the corridor when the nurse wheeled me away in the incubator. My mother was unconscious. My aunt ran after the nurse and asked her if it was a girl or a boy. Then my aunt ran back to my father who was waiting outside the operating theatre to inform him that it was a girl, and for this, my mother told me that I must be eternally grateful to my aunt, that I have a great debt to my aunt for what she did on the day I was born. This always confounded me, the way my mother put so much emphasis on what my aunt did to run after the nurse along the corridor of the hospital where I was born to discover that I was a girl and tell my father, how my mother didn’t think to highlight to me the importance of her own self at the moment of giving birth to me, but that my mother thought of my aunt’s doing a much more significant contribution to my birth than the one my mother made almost dying after the caesarean. I asked my mother about it, about why she went ahead with the birth, when she was warned after the several miscarriages that the diabetes was going to complicate the operation in her late-forties and healing the cut on her belly afterwards. She was asked not to take this risk to her life. My mother said that you need to have children so that there will be someone in the end to pour a drop of water into your mouth when you are dying.

*

I think it is this sky I will remember most. It looks like the day when fires burned in the oil refinery. After bombs echoed at midnight, for several days the sky looked like this, bathed in a radiance of orange, dimming and brightening as evening fell. My mother is looking at the orange sky, or maybe she isn’t. Maybe she is thinking about reaching the beginning, another life, a rebirth. When I call her, Amma, she turns her head to look at me. She is surrounded by my aunts, her four sisters, all in their seventies. They are big, cumbersome women. Their hearts are big, too. Their voices are even bigger.

I change my mother from her housecoat into one of those blue gowns they give at private hospitals, a pastel blue so tranquil like sky in a jar, she sits in a haze of blue. So tranquil, this woman who has always been so angry with us. She is a cloud today, not a storm.

The ward has others. A young man in bandaged legs on a sling. A motorbike accident, his mother tells me. An old woman in a bedjacket, a daughter by her side. A boy, coughing vehemently while a woman in a hijab rubs his chest.

There is a paper bracelet around my mother’s wrist. It has a name. The name is of a forest deity. A king built a temple in her name to repent for cutting the olive tree she occupied. It is the name that an astrologer approved for my mother’s birth time, for the way her stars and planets and moons aligned the day she was born. It is at this temple of her namesake deity that my mother once asked for a child. Around the atmosphere of the sthoopa of this temple where tooth relics of Buddha’s disciples lay, my mother told me that there were souls residing, souls who did a lot of merits in their past lives, astral bodies, searching for wombs to be reborn as humans, suitable wombs of women who did merits in their past lives, the womb of a good woman, for not all women are good and can become mothers, not all women have merits in their past lives to become mothers in this life, this is what my mother told me, that not all women could be the Buddha of their homes, the mother is the Buddha of the home. My mother went to the temple, offered flowers, and invited a soul to inhibit her womb. That soul has been me. My mother told me that I must have been floating there in my astral body, above the atmosphere of the temple of the forest deity, waiting for my mother’s invitation.

On the bedside table, under the lampshade by her hospital bed, pills in small, white, wasted envelopes rest. Unreadable pharmacist letters written on the covers in blue ballpoint. A meal tray lies with untouched jelly and pudding. The small marble Buddha statue, the size of her palm, rests in the mess, watching over her with kind eyes. She insists I keep the statue on the bedside table, the small statue from her shrine at home. It is a blessed statue. Hundred monks blessed it overnight with Buddhist chants. They sang under the Bo tree, which grew from a sapling of the one that has held Buddha’s back while he attained enlightenment, realised the truths of life, a nirvana. My mother wants the tiny statue there by her bedside when she comes out of the operating theatre.

My aunts bring with them an envelope full of pirith nool, chanted threads, from the monk they frequent in a temple in the suburbs. My mother tells them that she will not go into the operation without one of those chanted threads around her wrist. When my mother says this, I feel happy. I know she is hopeful about the operation, that she is not yet ready for a rebirth.

My aunts are laughing in good spirits despite the gloom and stench of disinfectant. My aunts tell me they are laughing at something that happened some time ago. A woman threw a bra at a foreign singer dancing like a worm on the stage at a concert in Galle Face. I tell them that the singer’s name is Enrique Iglesias, that I heard about this in Melbourne, and they say they don’t know his name, and neither it seems like this matter. They don’t even know how it came to this conversation. We don’t know who these powder babies are, Aney, we are from the village, we are village people, they remind me of their origins. They laugh some more to this.

My aunt, the one I have the great debt to, hushes us all. If we laugh too much, we’ll have to cry, she says.