Award for Indigenous Writing Shortlist

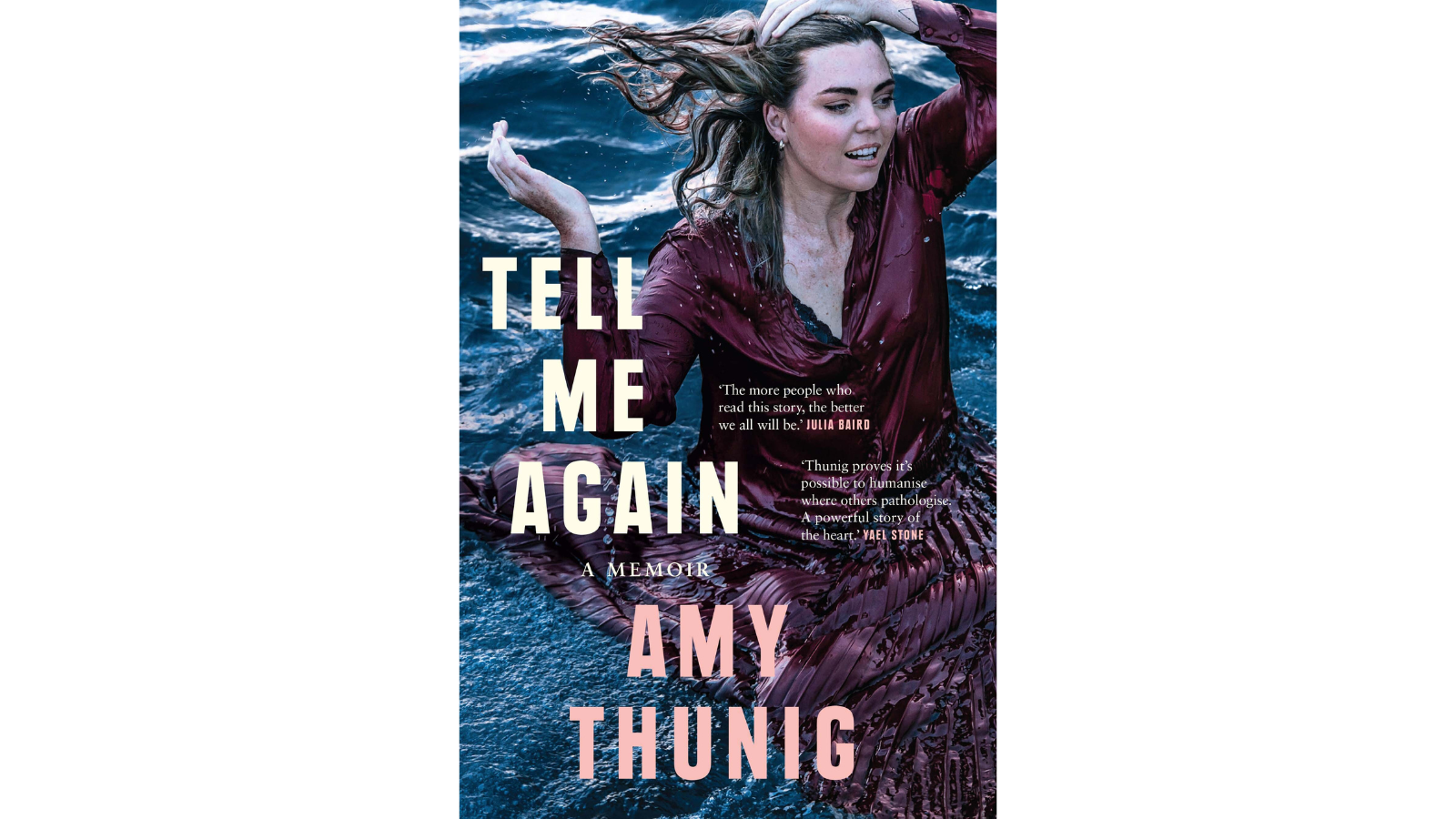

Title: Tell Me Again

Author: Amy Thunig

Publisher: University of Queensland Press

For years, Amy Thunig thought she knew all the details about the day she was born, often demanding that the story of her birth be retold. Years later, heavily pregnant with her own first child, she learns what really happened that day. It’s a tale that exemplifies many of the events of her early life, where circumstances sometimes dictated that things be slightly different from how they might seem – including what is meant by her dad being away for ‘work’ and why her legal last name differs from her family’s.

In this remarkable memoir, Amy narrates her journey through childhood and adolescence, growing up with parents who struggled with addiction and incarceration. She reveals the importance of extended family and community networks when your immediate loved ones are dealing with endemic poverty and intergenerational trauma. In recounting her experiences, she shows how the stories we tell about ourselves can help to shape and sustain us. Tell Me Again will captivate, move and inspire readers with its candour and insight.

Judges’ report

Thunig’s intimate and deeply personal memoir asks us as readers the complicated questions of how to wrestle with family, love, grief, pain, joy and systemic injustice. Their story is one of perseverance, told with the understanding of how the colonial systems work against those deemed to be at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

Their writing traverses time, creating space to breathe and reflect in between the stories of deep, unwavering love and the traumas that come with growing up in the face of adversary. A purposeful act of writing that does not concede to the eurocentric rules of memoir, Thunig plays with time and memory in a non-linear way that juxtaposes the hard truths with the most formidable acts of love. It is equally as joyous and painful to read, told with care, truth and honesty at its core.

Extract

Chapter 2

The Blue Mountains are home to many things: ancient sites, deep Dreaming, and numerous rehabilitation centres. Laying in a bed in one of these facilities, my mother, pregnant with me, wakes from a dream where she sees my father with another woman. She’s convinced it’s a vision, not a dream, and she sneaks out of the facility. She won’t stand for it.

~

A trip to rehab and in that time, Dad moved her in. Mum got out, found out, and broke into her own home to wait. She and Aunty cut the woman’s clothes up, and when the woman arrived back ‘home’ Mum pushed her down the stairs.

Eight months pregnant, Mum was still ready and willing to throw hands – an energy, we would later laugh, imbued to me from being within her at that time.

Did my name exist first or was it one of those cruel coincidences? Mum and Dad stayed together but when I came earthside a few weeks later, Mum wrote a new name, undiscussed, onto my birth certificate, and in place of ‘father’ simply wrote ‘unknown’. She used her last name instead of his, a small moment of revenge.

When I ask her how she chose ‘Amy’ in place of the longer elegant name that she and Dad had selected – had spoken over me in her belly all those months and turned out his ‘mistress’ happened to share – she said it was just a name she thought I could learn to spell easily in kindergarten. Just three letters. A-M-Y.

My naming and misnaming would weave itself into my life, and shape my experiences in ways my parents could never have anticipated.

A few years later a big loss hit our home. My younger brother was born but did not live for long. He came earthside, took to the breast, but at some point his breathing stopped and they simply whisked him away to the bowels of the hospital. They never brought him back.

Mum was left with empty hands and an aching heart. She received his little ankle bracelet, a photo of him, and was told to move on. It was over, done with, and somehow taboo to acknowledge him or grieve. With no support for her immense grief, Mum broke. Broke down. Too many people asking, ‘How much longer until that baby will be born?’ Then shunning her when she tried to mumble that actually he had been born, but he no longer lived.

Dad was away, serving eight years in prison for armed robbery – Mum pregnant with my brother when he was arrested. So he was left to grieve alone in lock-up over state lines, and she was left with two girls and a hole in her heart where Michael lived still. And when it got too much for her, she was smart enough and brave enough to take herself to the hospital and tell them she was not safe.

I was in the car too, and toddled in beside her when she arrived at the hospital. Whether it was her state or Dad’s incarceration, or perhaps my appearance or the fact she is a Murri woman, I do not know, but they wouldn’t listen when she explained that her father, my grandfather, was on the way to collect me.

Instead they sent for social services, and they organised my removal.

In a time before mobile phones, my pop had no idea he was racing against social services as he journeyed the route to the hospital. As fate – or rather traffic flows – would have it, Pop arrived at the same time as the people who were there to take me. The fire that raged in Pop’s belly as he realised what was happening that day still burns in his eyes: it comes up whenever the mess of my name is mentioned. He recognised that the people approaching me were there for my removal, and that he would need to fight.

Pop grabbed me, barely three years old. He got me in his arms but outnumbered by hospital staff and social services – threatened with the appearance of security and police – he couldn’t leave. I was his, and he was mine, and my mum had willed that I go with him: it was arranged, she had called, that was how he knew, that is why he came.

Still the staff were adamant and confident of their position in the argument that ensued. Yet before security was called, they revealed their error, the hospital’s error, which all linked back to Dad’s error and infidelity: they referred to me as Amy Teerman.

And that was never my name, not legally.

My mother kept no secrets from Pop, so he knew that my name was not legally Amy Teerman. The hospital staff’s claim was invalid on a child who did not legally exist. Pop made his connection clear with the simple showing of his driver’s licence. I was Amy Maccoll, my mother is Debra Maccoll, he is Malcolm Maccoll. Holding me tightly, he left, yelling that we were going and there was no way in hell we would wait for them to produce the paperwork that he still feared would disappear me.

Because I am of him, and he is of me. Our names were proof enough; the hospital staff stepped aside. The name Mum gave me out of anger, and a wish that I would have ease in kindergarten, meant I stayed with my sister, with our grandparents, until she was well again, or at least well enough to come home.

~

And on it went. When kindergarten enrolment came, they didn’t require a birth certificate – and why confuse a child or highlight their difference – so they just enrolled me as Amy Teerman, a name that claimed my father and linked me to my already-enrolled sister. They did throw in a sweet middle name ‘Lee’, which they claimed was short for ‘Cecily’, my nan’s name. A beautiful lie.

A lie that grew into my identity: Amy Lee Teerman, on every report, and eventually my Commonwealth Dollarmite student banking account. Because even in the poorer schools, where the kids lived in homes where ends hardly meet, the pressure to bank weekly was on.

When I moved into high school, I won awards, I gained glowing report cards, I added the occasional gold coin to that bank account, all under the name that was never actually mine. It grew and grew until the disconnect between who I was and my legal name was made clear. As I entered the workforce, the mess was not able to be cleaned up because none of us had the money to file legal documentation to change my name to match my identity.

It’s only a big deal if you make it one, Amy, Mum would remark when I would rage. And so, as with so many elements of my childhood, it was their mess but I was the one who had to live with it.

I didn’t yet understand the gift of protection the name had offered me that day at the hospital, or that my parents were just doing their best in moments of overwhelm.

Years later, when the day came that I married, I wasn’t thinking of feminism, or family pride in names, or legal markers to bloodlines. I was thinking how nice it would be to no longer be regularly reminded of a name that is seeded in my father’s infidelity, and linked with stories of trauma and pain. I was thinking of how much I love my stepdaughter and how, although we are not bonded in blood, we could be bonded in name. I was thinking of what was best for me, and my family, at that time. And so I told that husband I would agree to take his name, but should the day come where we divorced, I would keep it: I would publish under that name; it would become and remain mine.

So when people ask me why I chose to take on that name, when they throw shade at my identity because of this, I feel ready to throw hands like my mum did that day in the stairwell; because it would be easier than explaining the story and trauma of what is in a name.

About the author

Dr Amy Thunig (B.Arts, M.Teach, PhD) is a Gomeroi/Gamilaroi/Kamilaroi yinarr (woman) and mother who resides on the unceded lands of the Awabakal peoples. An academic in the field of education, Amy is also a Director at Story Factory in Redfern, and in 2019 gave their TEDx talk: ‘Disruption is not a dirty word’. As well as being on various committees and councils, Amy is a media commentator and panellist, regularly appearing on television programs such as ABC’s The Drum, and writing for publications such as Buzzfeed, Sydney Review of Books, IndigenousX, The Guardian and more.

Related Posts

Read

Anne-Marie Te Whiu Receives The Next Chapter Alumni Poetry Fellowship

2 Apr 2024

Read

What's on in April: Resident Organisation Round Up

28 Mar 2024

Read

Blak & Bright First Nations Literary Festival returns in 2024

7 Mar 2024

Read

What's on in March: Resident Organisation Round Up

29 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: International

23 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: The Rooms

23 Feb 2024

Share this content