VPLA 2023

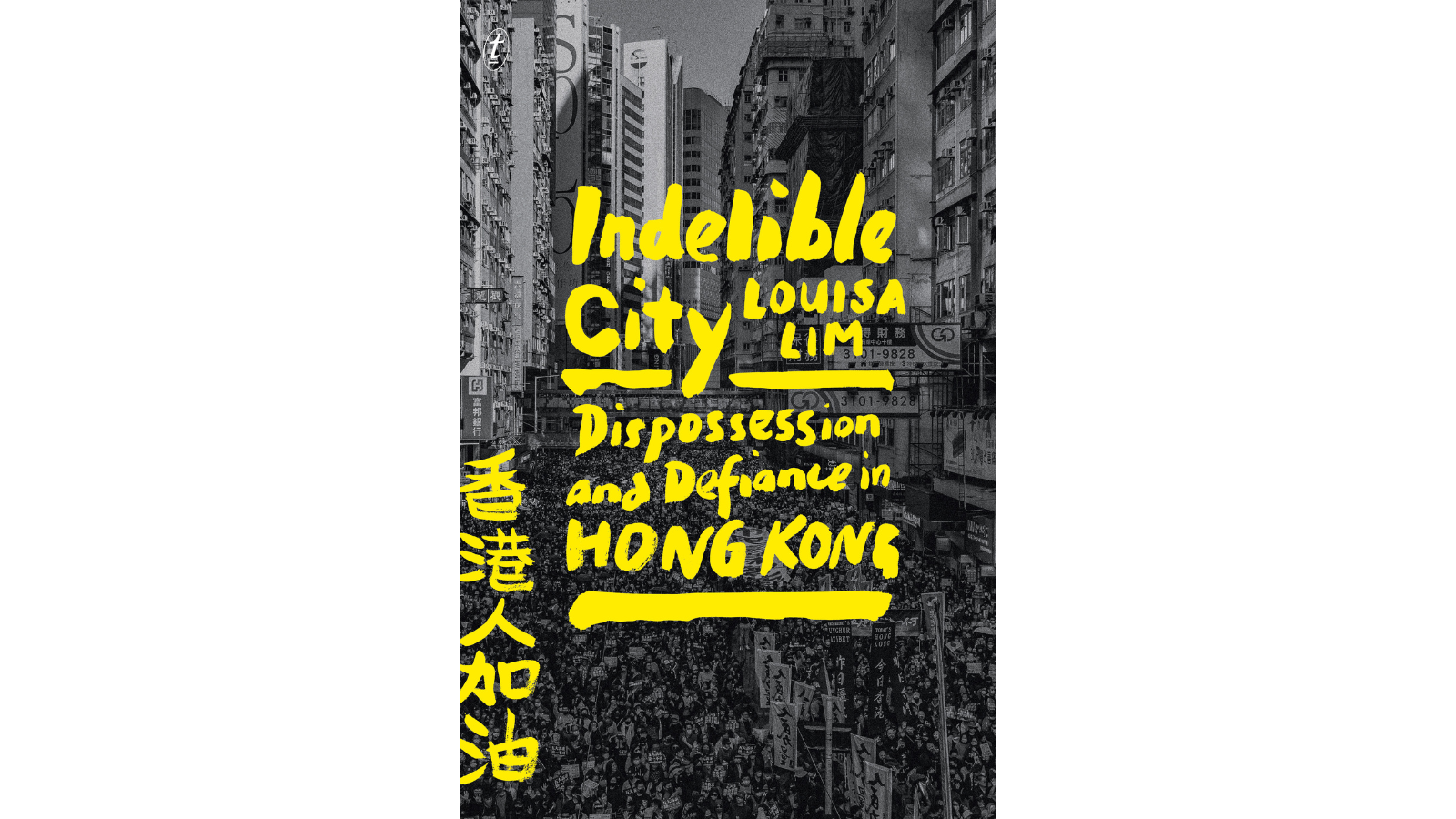

Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong

Non-Fiction Award Shortlist

Title: Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong

Author: Louisa Lim

Publisher: Text Publishing

The story of Hong Kong has long been obscured by competing myths: to Britain, a ‘barren rock’ with no appreciable history; to China, a part of Chinese soil from time immemorial that had at last returned to the ancestral fold. To its inhabitants, the city was a place of refuge and rebellion, whose own history was so little taught that they began myth-making their own past.

When protests erupted in 2019 and were met with escalating suppression from Beijing, Louisa Lim – raised in Hong Kong as a half-Chinese, half-English child, and now a reporter who had covered the region for a decade – realised that she was uniquely positioned to unearth Hong Kong’s untold stories.

Lim’s deeply researched and personal account is startling, casting new light on key moments: the British takeover in 1842, the negotiations over the 1997 return to China, and the future Beijing seeks to impose. Indelible City features guerrilla calligraphers, amateur historians and archaeologists who, like Lim, aim to put Hong Kongers at the centre of their own story.

Wending through it all is the King of Kowloon, whose iconic street art both embodied and inspired the identity of Hong Kong – a site of disappearance and reappearance, power and powerlessness, loss and reclamation.

Judges’ report

Indelible City is a well-researched and expansive hybrid work that refuses to be categorised. Early in the book, reflecting on Hong Kong’s current political crisis, Lim asks, “How to practice ethical journalism under the circumstances? […] Could I remove myself from the picture when the picture was already part of me?” And so we have a book that is not quite memoir, not quite investigative journalism, not quite history—a text that, while it didn’t set out to do so, debunks the objective fallacy that runs rampant in journalism. As she dismantles the received wisdom about Hong Kong’s history alongside the telling of her own family history, juxtaposed with her admiration for the King of Kowloon, Tsang Tsou-choi, Lim’s closeness to the subject makes it all the more compelling. This is a text that looks closely at the past and tells a story about the present in the hopes of changing the course of the future.

Extract

Prologue

I was squatting on the roof of a Hong Kong skyscraper, sun blazing on my head, sweat dripping into my eyes, painting expletive‑laden Chinese characters onto a protest banner eight stories high and wondering if I had just killed my career in journalism. The air was soupy with heat, and through the haze I could see a satisfying Tetris‑scape of rooftops packed so tight they seemed to interlock. I’d come to the rooftop to interview a secret cooperative of guerrilla sign painters who specialized in producing mammoth pro‑democracy banners to be slung from Hong Kong’s highest peaks. But as I watched, my fingers itched to grab a paint brush and join in.

It was the autumn of 2019, the day before China’s National Day, commemorating the seventieth anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. For months, millions of people had marched through Hong Kong’s streets, in the biggest and most sustained anti‑government protests the territory had ever seen. After 155 years as a British colony, Hong Kong had been returned to China in 1997, in an unprecedented transition of sovereignty. Although Beijing had vowed that Hong Kong could preserve its way of life for fifty years— until 2047—China was now threatening to ram through legislation that would renege on that promise.

The secret band of calligraphers had been busy deploying their team of rock climbers to scale Hong Kong’s crags in the dead of night, so that people woke up to gigantic signs exhorting them to “Take to the Streets to Oppose the Evil Law” or “Fight for Hong Kong.” The sheer scope of the banners turned the territory itself into a canvas and reinvigorated the protest movement when morale was ebbing. I’d always been fascinated by the audacity of the sign painters, but I had no idea who they were or how to get in touch with them. That morning, someone who knew of my obsession had contacted me out of the blue to invite me to watch them in action. It was an offer I couldn’t refuse.

The sunbaked rooftop of this tall building offered both the privacy and the expanse necessary to lay out the huge banners and dry them. There were seven sign painters. I had promised not to divulge any details that might expose their identities, but I was surprised that instead of the young, athletic radicals of my imagination, they were older men and women whose familiarity with one another was evident in the wordless efficiency of their interactions. Working quickly, they unfolded a gigantic bolt of thick black cotton, then used their feet to stamp the material flat on the roof in a brisk, communal dance. They placed rocks along the edges to hold the cloth still. Then an elderly calligrapher began sketching out the characters in white chalk. Moving with a fluid grace, the writer’s entire body mirrored the strokes of a calligraphy brush dancing across the fabric as the piece of chalk dipped and curved, tracing the outline of four enormous Chinese characters.

As the final ideogram took shape, I couldn’t help but snort with laughter. The words the calligrapher was so carefully inscribing on the banner were 賀佢老母, a sweary and wholly untranslatable pun in Cantonese, the dominant language spoken in Hong Kong and parts of southern China. A literal translation would be “Celebrate their mother!” but this was actually a pun playing on the most popular Cantonese insult: 屌你老母, or “Fuck your mother!” So the actual meaning of the banner was something along the lines of “Fuck your motherfucking National Day celebrations!” In other words, the slogan was calculated to cause maxi‑ mum offense, by mocking the massive military parade to be held in Beijing and at the same time underscoring that Hong Kongers did not consider themselves part of the People’s Republic of China. It was an irreverent slap in the face that was simultaneously laugh‑out‑loud funny and deadly serious, not least because, if caught, the sign painters could face jail time.

I watched as they grabbed their pots of paint and silently squatted beside the banner to begin filling in the characters, struggling with my desires. For months, my dual identities as a Hong Konger and a journalist had been engaged in a silent contest of wills, as I tried to safeguard my professional neutrality. This was becoming ever harder as the familiar world I’d grown up in, with all its predictable certainties, collapsed around me. On the surface it was still the same city pulsing with energy from the shoals of people surging through the skyscraper‑lined streets, the beeping signals at zebra crossings, the LED signs jostling for airspace, the acrid dried‑fish reek of a Chinese medicine shop melding with the rich bark‑smoke aroma of a stall selling tea‑steeped eggs. But the apparatus beneath this sensory cacophony was shifting in ways I could no longer ignore.

The police, instead of being guarantors of security, were behaving like violent thugs who beat and arrested children for wearing a particular color, or for standing in a particular street at a particular time, or for nothing at all. The courts, instead of being neutral arbiters of the law, were handing down political verdicts disqualifying popularly elected legislators from the legislature and imprisoning people for peaceful protests.

The government officials, instead of enacting and administering policy, had disappeared from view and were limiting their interactions with the populace to violence meted out by the police on their behalf. Overnight the world had turned upside down.

About the author

Louisa Lim is the author of The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited (2014), which was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize and the Helen Bernstein Book Award for Excellence in Journalism. She covered China and Hong Kong for a decade as a correspondent for the BBC and NPR, and has reported for the New York Times, Washington Post and Guardian. Raised in Hong Kong, she lives in Australia with her two children and teaches at the University of Melbourne.

Related Posts

Read

Anne-Marie Te Whiu Receives The Next Chapter Alumni Poetry Fellowship

2 Apr 2024

Read

What's on in April: Resident Organisation Round Up

28 Mar 2024

Read

Blak & Bright First Nations Literary Festival returns in 2024

7 Mar 2024

Read

What's on in March: Resident Organisation Round Up

29 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: International

23 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: The Rooms

23 Feb 2024

Share this content