Speaking back to absences and absurdities

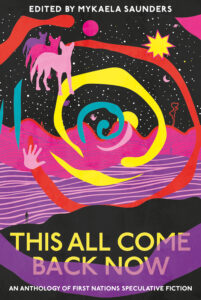

We spoke to anthology editor Mykaela Saunders about subverting and reconfiguring expectations in This All Come Back Now, an anthology of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander speculative fiction that centres First Nations communities, cultures and creativity.

This All Come Back Now is dedicated to ‘those who are dreaming up new ways to tell our stories and… pouring them back into the river of our collective culture for the benefit of all’. Why is it so important to champion and share stories like the ones included in this collection?

For the last few hundred years, Australia has attempted to assert its own legitimacy by erasing Aboriginal stories, and for most of its history the settler-colonial publishing industry has been instrumental in this by keeping our stories out of books. Things have recently gotten better for our stories, but usually only for a certain type of Indigenous story, which is often those that can be easily commodified and sold to a non-Indigenous readership. Stories like the ones in This All Come Back Now – stories that are strange and weird and don’t fit neatly into any boxes, stories that are not written for the white gaze, stories that assert our sovereignty and survivance throughout all times – these are stories that are just as important as more mainstream ones, and it is crucial that our people have access to a diversity of storytelling, just like every other culture enjoys.

Was there a particular moment that prompted you to put this collection together?

There have been several moments, which, when added together, is more than the sum of its parts. Firstly, I spent the last few years studying Indigenous speculative fiction for my doctorate degree, and I wanted to create a collection that showcased the breadth of incredible stories I was reading. In this period I also read so much non-Indigenous spec fic which uses Indigenous characters as magical plot twists, or otherwise erases us entirely, and I wanted to speak back to all those absences and absurdities. Finally, I read a few spec fic anthologies from other cultures, and I wanted one to exist for our own people – so other blackfellas could enjoy an anthology of weird stories too.

How long have you been reading and writing speculative fiction?

I began writing my own spec fic in 2017, as part of my doctorate degree at the University of Sydney, after a lifetime of loving it. I’ve been reading, watching and listening to various forms spec fic for as long as I can remember, though I haven’t always articulated my love of strange and speculative yarns using the term ‘spec fic’. Ever since I was little I’ve always loved old Aboriginal stories, many of which use literary devices that are often referred to as ‘fantastical’ or ‘speculative’ – magic, time warps, technology, ghosts, spirits, devils and other wonderful entities. I also really loved fairy tales and spiritual stories from other cultures.

Music has always shaped my love of spec fic too. Ever since I was young I’ve always gravitated to the more heavy metal types of films, especially the Mad Max and Terminator movies. I was obsessed with the Dead Kennedys in high school and their satirical song ‘California Uber Alles’ always struck me as a horrible, dystopian world. I love all the Afro-futurist musicians from Sun Ra to Janelle Monae, and I’ve also been influenced by so many weird hip hop, hard techno and power metal bands who build whole sci fi and fantasy worlds through their music.

In what ways does this collection demonstrate First Nations resilience and resistance, and how does it challenge colonialist traditions in genre fiction?

This All Come Back Now is powerful purely because it exists in a very white-dominated spec fic landscape. Although this is a world-first, it doesn’t give me any pleasure that it hasn’t been done before. I think that’s an indictment of the Australian literary world rather than a thing to big note about. This is a sovereign-minded collection of stories which refuses to make itself safe and small for the consumption of others. The stories are also so funny and cheeky and clever. As esteemed Wiradjuri writer and scholar Dr Jeanine Leane so generously put it in her rigorous appraisal of the book for the Sydney Review of Books,

“This All Come Back Now is an act of radical subversion and intellectual sovereignty. The limits of Western rationalism, claims to objectivity, universalism, and the singularity of binaries are savaged and dismantled through the power of local knowledges, parallel existences, life forms other than human and alternative planes of being. In this collection First Nations writers transform and reclaim a genre that has defined Western attitudes towards race, colonialism, and technology into a vehicle of First Nations continuance, resilience, and resistance.”

What do you mean when you describe Indigenous speculative fiction as a ‘big and porous basket that holds all the most slippery types of stories together’?

I think of Indigenous spec fic genres as ‘slippery’ as they are rooted in consensus reality while swimming in and out of it. To me, spec fic includes science fiction, climate fiction, alternate history, futurism, post/apocalyptic fiction, utopian and dystopian fiction, fantasy, horror, gothic fiction, surrealism, magic realism, and slipstream fiction. These are the kinds of stories that take place outside the bounds of said consensus reality, but could maybe happen, give or take a few tweaks of said reality. For example, a ghost story will be true in a reality where ghosts are real. The same goes with wizards in a fantasy story. Many of the above genres overlap. For example science fiction is a genre that thinks about the impacts of technology on society. This is often futuristic too, but not always. Futurism is any type of spec fic that thinks about near or far futures, based on the known of the now. This is where the ‘speculative’ part of the fiction comes from – the use of conjecture to think about what may come out of what is already here. Any thinking about any future is speculative thinking.

You’re taking part in The Next Chapter scheme this year. Could you tell us about the work you’re developing through the scheme?

I’m working on my psychedelic nightmare of a novel Last Rites of Spring. The narrative present of the story takes place over one day, and mostly in one small room in the head of one protagonist, but the story cycles in and out of the past and future, and to other places in the present too. I wrote the first draft in 2017 when I was a much worse writer, and it was shortlisted for the David Unaipon Award in 2020. I’ve spent the last few months of my fellowship rewriting the story, right down at the sentence level. It’s intensive work but I’m so happy to do it, because I love the story and the protagonist so much, and she deserves a second chance at life – by rendering the story in much better writing I will be able to do it the justice it deserves!

This All Come Back Now: First Nations Speculative Fiction will take place at the Wheeler Centre on Tuesday 17 May 2022.

Related Posts

Read

Anne-Marie Te Whiu Receives The Next Chapter Alumni Poetry Fellowship

2 Apr 2024

Read

What's on in April: Resident Organisation Round Up

28 Mar 2024

Read

Blak & Bright First Nations Literary Festival returns in 2024

7 Mar 2024

Read

What's on in March: Resident Organisation Round Up

29 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: International

23 Feb 2024

Read

Hot Desk Extract: The Rooms

23 Feb 2024

Share this content